The word "bull's-eye" refers to the small black or red circle in the exact center of a target.

The word "bull's-eye" refers to the small black or red circle in the exact center of a target. Each one of us has unique talents in a variety of different areas. For example, some of us may be excellent golfers, or excellent musicians, or excellent cooks, or excellent mechanics, or excellent jugglers, or excellent managers. But no one is gifted in every possible skill area.

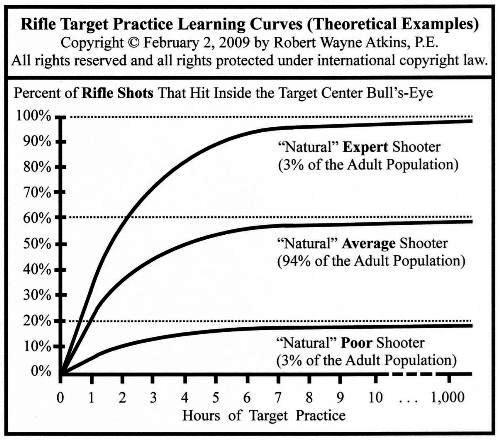

Each one of us has unique talents in a variety of different areas. For example, some of us may be excellent golfers, or excellent musicians, or excellent cooks, or excellent mechanics, or excellent jugglers, or excellent managers. But no one is gifted in every possible skill area. Almost everyone could benefit from training in any area in which they are not already familiar. For example, if you have never played golf then a few hours of basic golf lessons could help you to significantly improve your average score on the golf course. However, once you reach your natural "performance plateau" then additional golf lessons will only result in relatively insignificant improvements in your golfing abilities.

Almost everyone could benefit from training in any area in which they are not already familiar. For example, if you have never played golf then a few hours of basic golf lessons could help you to significantly improve your average score on the golf course. However, once you reach your natural "performance plateau" then additional golf lessons will only result in relatively insignificant improvements in your golfing abilities.

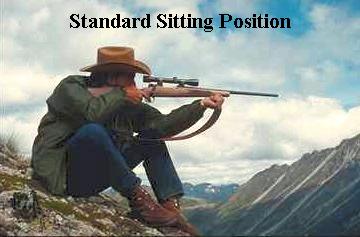

| Position | Accuracy | Ease to Assume | Visibility |

| Prone | Best | Slowest | 15 Inches |

| Sitting | Good | Slow | 30 Inches |

| Kneeling | Okay | Fast | 42 Inches |

| Standing | Worst | Fastest | 64 Inches |

Breathing: As you breathe your lungs and your chest area expands and contracts. If you have your rifle butt against your shoulder then your normal breathing will cause the front muzzle of your rifle to rise and fall. In other words, you will not be able to keep your scope cross hairs properly centered on the target bull's-eye.

Breathing: As you breathe your lungs and your chest area expands and contracts. If you have your rifle butt against your shoulder then your normal breathing will cause the front muzzle of your rifle to rise and fall. In other words, you will not be able to keep your scope cross hairs properly centered on the target bull's-eye.

A handgun is only accurate at a very short distance, usually within 25 feet or less to your target (or much closer if you are shooting a relatively large caliber such as the 44 Magnum). If you are an average shooter and you are shooting a handgun in a caliber that you can control then you should be able to hit somewhere on the paper target with most of your shots if you are within twenty-feet of the target. However, do not expect to see a lot of bull's-eyes. Any shots inside the bull's-eye are probably due to random chance, unless you are shooting a very low caliber bullet with negligible recoil.

A handgun is only accurate at a very short distance, usually within 25 feet or less to your target (or much closer if you are shooting a relatively large caliber such as the 44 Magnum). If you are an average shooter and you are shooting a handgun in a caliber that you can control then you should be able to hit somewhere on the paper target with most of your shots if you are within twenty-feet of the target. However, do not expect to see a lot of bull's-eyes. Any shots inside the bull's-eye are probably due to random chance, unless you are shooting a very low caliber bullet with negligible recoil. Handgun Laser: It is okay to put a laser under the barrel of a handgun to help you more quickly and accurately aim your handgun at the target. Some individuals recommend against the installation of a laser on a self-defense handgun because it may reveal your location to armed robbers who are invading your home in the middle of the night. However, if you will think about this for a moment, the first time you fire your handgun at night the muzzle blast will instantly show everyone exactly where you are. If you are using your handgun for emergency self-defense in a highly stressful life-threatening situation when criminals are shooting at you, then my opinion is that it would be advantageous to have a laser to quickly assist you in realigning your handgun on the "kill zone" of each attacker so you could end the conflict as quickly as possible with your being the only surviving participant. A laser would allow you to hold your handgun slightly to one side as you fire it. This means you would not need to keep your handgun directly in front of you so you could "aim" down the barrel of your handgun at your assailants. If your attackers were firing at the muzzle blast from your handgun then it is possible that their bullets will miss you out to the side that you are holding your handgun. However, this is just my opinion and you may follow whatever advice you choose. If you install a laser under the barrel of your handgun then you will need to follow the instructions that come with that laser and adjust it so that it points to the approximate location your handgun bullets hit when you fire your handgun at a target. It would probably also be a good idea to practice shooting your handgun while holding it in one hand out to one side of your body so you can develop some skill in this type of shooting using your handgun and your laser to place your bullets in the "kill zone" of the paper target.

Handgun Laser: It is okay to put a laser under the barrel of a handgun to help you more quickly and accurately aim your handgun at the target. Some individuals recommend against the installation of a laser on a self-defense handgun because it may reveal your location to armed robbers who are invading your home in the middle of the night. However, if you will think about this for a moment, the first time you fire your handgun at night the muzzle blast will instantly show everyone exactly where you are. If you are using your handgun for emergency self-defense in a highly stressful life-threatening situation when criminals are shooting at you, then my opinion is that it would be advantageous to have a laser to quickly assist you in realigning your handgun on the "kill zone" of each attacker so you could end the conflict as quickly as possible with your being the only surviving participant. A laser would allow you to hold your handgun slightly to one side as you fire it. This means you would not need to keep your handgun directly in front of you so you could "aim" down the barrel of your handgun at your assailants. If your attackers were firing at the muzzle blast from your handgun then it is possible that their bullets will miss you out to the side that you are holding your handgun. However, this is just my opinion and you may follow whatever advice you choose. If you install a laser under the barrel of your handgun then you will need to follow the instructions that come with that laser and adjust it so that it points to the approximate location your handgun bullets hit when you fire your handgun at a target. It would probably also be a good idea to practice shooting your handgun while holding it in one hand out to one side of your body so you can develop some skill in this type of shooting using your handgun and your laser to place your bullets in the "kill zone" of the paper target. Firearm caliber is an important consideration. You will need a bullet that is big enough to terminate whatever type of wild game you may be hunting. But a really big caliber is not appropriate for smaller game animals, such as raccoons and opossums. The amount of information currently available on each of the different calibers is truly overwhelming.

Firearm caliber is an important consideration. You will need a bullet that is big enough to terminate whatever type of wild game you may be hunting. But a really big caliber is not appropriate for smaller game animals, such as raccoons and opossums. The amount of information currently available on each of the different calibers is truly overwhelming. All firearms have a maximum possible distance if the bullet is fired at an angle up into the air and it covers an arched trajectory until it eventually falls to the ground. This distance is an interesting statistic but it is of little practical value because the bullet has lost almost all of its power and energy when it finally makes contact with the ground.

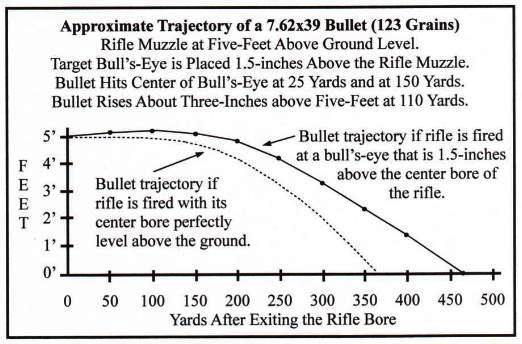

All firearms have a maximum possible distance if the bullet is fired at an angle up into the air and it covers an arched trajectory until it eventually falls to the ground. This distance is an interesting statistic but it is of little practical value because the bullet has lost almost all of its power and energy when it finally makes contact with the ground. There are four factors that will help you determine the best distance to "zero" or set your riflescope cross hairs:

There are four factors that will help you determine the best distance to "zero" or set your riflescope cross hairs:

| Rifle Caliber | First Bull's-eye | Second Bull's-Eye | Maximum Trajectory | Minimum Trajectory | 800 Foot-Pounds |

| 223 or NATO 5.56x45 | 25 Yards | 175 Yards | + 1.0 inch at 95 Yards | - 1.0 inch at 200 Yards | 150 Yards |

| 7.62x39 | 25 Yards | 150 Yards | + 1.5 inches at 110 Yards | - 1.5 inches at 175 Yards | 240 Yards |

| 308 or NATO 7.62x51 | 25 Yards | 220 Yards | + 3.0 inches at 125 Yards | - 3.0 inches at 260 Yards | 600 Yards |

Safety Precaution: Larger caliber rifles generally have more recoil than smaller caliber rifles. If you place your eye too close to the scope then when the rifle fires it will recoil backwards and the scope will move backwards with the rifle and you will get a serious "black eye" or something worse. Therefore always:

Safety Precaution: Larger caliber rifles generally have more recoil than smaller caliber rifles. If you place your eye too close to the scope then when the rifle fires it will recoil backwards and the scope will move backwards with the rifle and you will get a serious "black eye" or something worse. Therefore always:

| Distance to Target = | 25 Yards | 50 Yards | 100 Yards | 200 Yards |

| Type C Scope = | 1/16 Inch | 1/8 Inch | 1/4 Inch | 1/2 Inch |

| Type D Scope = | 1/8 Inch | 1/4 Inch | 1/2 Inch | 1 Inch |

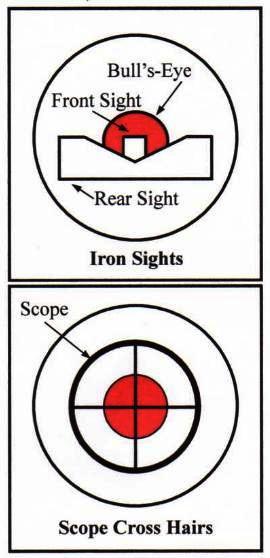

Iron Sights: Most rifles have iron sights permanently attached to the top of the rifle. The design of those iron sights vary somewhat but the most common design is shown in the illustration on the right. Point the rifle at the target and align the top of the front sight so that it is level with the right and left tops of the rear sight as shown in the illustration. Depending on the size of the target bull's-eye and your distance from the target, it may be necessary to align the very bottom of the target bull's-eye with the straight line formed by your front and rear sights. This is necessary because the bull's-eye may appear so small at 100 yards that it is difficult to see and it may be completely covered by your front and rear sights if you try to center those sights on the center of the bull's-eye.

Iron Sights: Most rifles have iron sights permanently attached to the top of the rifle. The design of those iron sights vary somewhat but the most common design is shown in the illustration on the right. Point the rifle at the target and align the top of the front sight so that it is level with the right and left tops of the rear sight as shown in the illustration. Depending on the size of the target bull's-eye and your distance from the target, it may be necessary to align the very bottom of the target bull's-eye with the straight line formed by your front and rear sights. This is necessary because the bull's-eye may appear so small at 100 yards that it is difficult to see and it may be completely covered by your front and rear sights if you try to center those sights on the center of the bull's-eye. Depending on the direction from which the wind is blowing the wind will have the following impact:

Depending on the direction from which the wind is blowing the wind will have the following impact:| Bullet Caliber | 100 Yards | 200 Yards | 300 Yards |

| 223 (5.56x45) | 0.9 Inch | 3.6 Inches | 8.5 Inches |

| 7.62x39 | 0.8 Inch | 3.4 Inches | 8.0 Inches |

| 308 (7.62x51) | 0.7 Inch | 3.2 Inches | 7.5 Inches |

| 30-06 | 0.7 Inch | 3.0 Inches | 7.0 Inches |

| --------------- | -------- | -------- | -------- |

| Average "Rounded" | 1.0 Inch | 3.0 Inches | 8.0 Inches |

Only a few of your hunting shots will be on perfectly level ground. Most of your shots will be fired at a game animal that is a little above or a little below the center bore of your rifle. If the animal is only five or ten feet above or below you, then you can safely ignore the difference in elevation and simply align your scope cross hairs in the center of the animal's "kill zone" the same as if you were shooting over level ground.

Only a few of your hunting shots will be on perfectly level ground. Most of your shots will be fired at a game animal that is a little above or a little below the center bore of your rifle. If the animal is only five or ten feet above or below you, then you can safely ignore the difference in elevation and simply align your scope cross hairs in the center of the animal's "kill zone" the same as if you were shooting over level ground. If you can afford it then you should consider investing in a Multiple Purpose Gun Cleaning Kit that could be used to clean almost any type of handgun, rifle, or shotgun, including the smallest BB or pellet rifle up to the 50 caliber BMG (Browning Machine Gun). Although you may not currently have an application for all the gun cleaning accessories in this kit you may discover that you will eventually need many of them if you continue to acquire more firearms during your lifetime. The Universal 61-Piece Gun Cleaning Kit in the picture on the right is available at some WalMarts in their Sporting Goods section for approximately $40.

If you can afford it then you should consider investing in a Multiple Purpose Gun Cleaning Kit that could be used to clean almost any type of handgun, rifle, or shotgun, including the smallest BB or pellet rifle up to the 50 caliber BMG (Browning Machine Gun). Although you may not currently have an application for all the gun cleaning accessories in this kit you may discover that you will eventually need many of them if you continue to acquire more firearms during your lifetime. The Universal 61-Piece Gun Cleaning Kit in the picture on the right is available at some WalMarts in their Sporting Goods section for approximately $40.

The one additional tool kit that you should seriously consider buying is a special Gunsmith Screwdriver Set that contains all the special screwdrivers, hex wrenches, and other special tools that you will normally need to properly disassemble and reassemble your firearms without damaging them.

The one additional tool kit that you should seriously consider buying is a special Gunsmith Screwdriver Set that contains all the special screwdrivers, hex wrenches, and other special tools that you will normally need to properly disassemble and reassemble your firearms without damaging them.

| Distance = | 100 Yards | 200 Yards | 300 Yards |

| Wind Drift = | 1 Inch | 3 Inches | 8 Inches |

| Wind Speed = | 5 mph | 10 mph | 15 mph | 20 mph | 25 mph | 30 mph |

| Multiply By = | 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 3.0 |

| Rifle Caliber | First Bull's-eye | Second Bull's-Eye | Maximum Trajectory | Minimum Trajectory | 800 Foot-Pounds |

| 223 or NATO 5.56x45 | 25 Yards | 175 Yards | + 1.0 inch at 95 Yards | - 1.0 inch at 200 Yards | 150 Yards |

| 7.62x39 | 25 Yards | 150 Yards | + 1.5 inches at 110 Yards | - 1.5 inches at 175 Yards | 240 Yards |

| 308 or NATO 7.62x51 | 25 Yards | 220 Yards | + 3.0 inches at 125 Yards | - 3.0 inches at 260 Yards | 600 Yards |